tchotchke #46: Has being good at admin ruined my life?

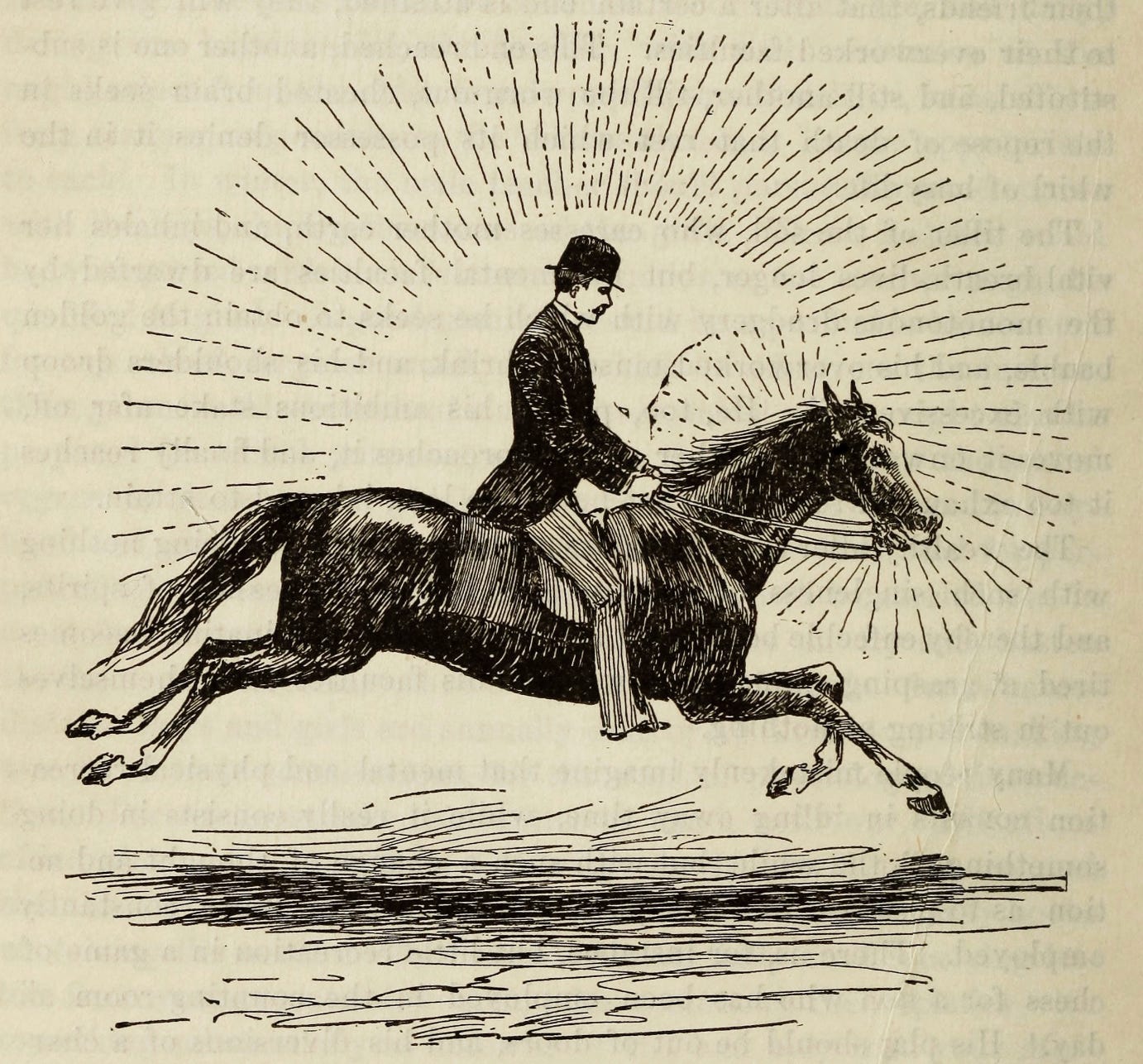

The galloping life of the mind.

I love emails, and it’s a problem. I love emails and, to a lesser extent spreadsheets; I love producing large-scale events, orchestrating complicated multi-author publications, organizing merchandise sales, starting groups and clubs and podcasts and brands, buying domain names and building websites, delegating tasks and managing a team… all good things, right?

But when I reflect on over 10 years of successful admin—the first event I personally organized was a Homestuck prom in my hometown in 2013!—I wonder if, perhaps, it has fatally doomed me.

This reflection was prompted by Virginia Woolf’s essay “Middlebrow,” written in the 1930s and published posthumously in 1942. The piece was her salvo in the Battle Of The Brows, an ongoing critical back-and-forth which began before the Second World War and continued well into the 1960s, as the greatest minds of their generations tried to figure out if mass culture was bad for humanity and if so, just how bad.

Her take on that issue is typically and endearingly snobby, but I specifically was interested in her definitions of the highbrow and the lowbrow as species of people.

Highbrows, she writes, “for some reason or another, are wholly incapable of dealing successfully with what is called real life” — too busy “[riding] his mind at a gallop across country in pursuit of an idea” and driving the avant-garde forward with their art.

Highbrows like Woolf herself, like “Shakespeare, Dickens, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Charlotte Brontë, Scott, Jane Austen, Flaubert, Hardy or Henry James” lead lives of art, lives of the mind, and meanwhile are utter messes on any given day. They don’t follow trends, they don’t know nor care about having the “right thing” to wear or do or say, for that is the province of the distasteful striving middlebrow.

Domestically and administratively, Woolf implies that the labor of the lowbrow (of any class, for she claims that she has known highbrow charwomen as well as lowbrow duchesses) is necessary to rely on to sustain the galloping genius of the highbrow.

This sort of relates to the ideas she expressed in A Room Of One’s Own, namely that a certain level of financial and domestic independence is necessary for the emergence of genius. But she also seems to be making an idiosyncratic case for the inconvenient aspects of a true artist’s existence; the necessity of a certain kind of incompetence.

And it scared me a little. Have I been doomed by competence? What if I die a better administrator than an artist?

I wouldn’t say that the kind of admin I enjoy is wholly uncreative: far from it. It requires a flexibility of mind and the ability to continuously generate ideas; it requires social confidence and the ability to imagine a world where the crazy thing I want to do actually happens, and then manifest that world. But the fact that I am good at it and have gotten better at it seems to have put me in a corner.

There will always be work for someone who is good at getting things done, email- and spreadsheet-wise; there will not always be work for an artist, especially one who is not by any means an outstanding genius or a voice of a generation. It’s so much more lucrative—and sensible—to be a good emailer, professionally, than a mediocre writer!

This stings especially because in some ways I am the kind of incompetent person Woolf describes as a highbrow: but in my case, instead of that leading me to a life of the mind, it simply means I have a disastrously disorganized apartment, am bad at cooking and dating, and can be found taking the path of least resistance towards pleasure (lowbrow mass culture, which I have built my career around publicly enjoying) and money (I am gainfully employed in a full-time editorial marketing job).

If I were only capable of being an artist, I would have had no choice but to try to become one: much like my father, who dropped out of college twice, turned down big corporate radio gigs, and generally avoided lucrative prospects in favor of the peripatetic and risky lifestyle that often jeopardized the family finances but nevertheless maximized the time he would spend actually playing his instrument, which was until the end of his life really and truly the only thing he cared about.

He was an excellent producer, a brilliant and popular radio host, a writer and critic of spectacular talent, but that wasn’t what he wanted to do, so he didn’t do it; he wanted be a musician and he was one; he lived an artistic, highbrow, galloping, chaotic life.

Meanwhile since childhood I have ostensibly really wanted to be a showrunner or novelist or a singer but, pathologically averse to sacrifice and effort and (this is important and worthy of an entire separate essay) attention and critique, I am none of those things. But I am very good at admin.

The disappearance of the relevance of the highbrow/lowbrow distinction in the 21st century has been explained by writers more versed in cultural theory than I; but the continued importance of Woolf’s short sardonic piece lies in her explication of such thing as a highbrow temperament, a personality of genius, which comes off to a modern reader as amounting to some kind of neurodivergence, some critical difference which contributes to single-mindedness and fierce independence in an artistic sense even as it makes them “wholly incapable” of handling real life.

Competence, conversely, makes for an un-genius life, one whose destiny might lie instead in competently facilitating the genius lives of others: not a bad life, I emphasize, and one I personally know to be full of joys and excitement and proud accomplishment, but is it my ultimate goal?

And should it be, after all? Would it be so terrible after all to avoid the many, many pitfalls and failures of my father, and of all the other artists who chase ideas across uneven and perilous country?

I mean Shakespeare was part owner of the Lord Chamberlain's men, in addition to being an actor and playwright. Virginia, I suspect, was indulging herself in some copium (and as a deeply incompetent person myself, I sympathise). I expect you'll have a culture defining media empire, in addition to your own stellar cultural contributions.

When are you going to grad school? You had said you want to continue your studies elsewhere. You won’t have time to worry about all this stuff.