Well, I’m really mad about something online again so it’s time to crack open the old newsletter and kvetch.

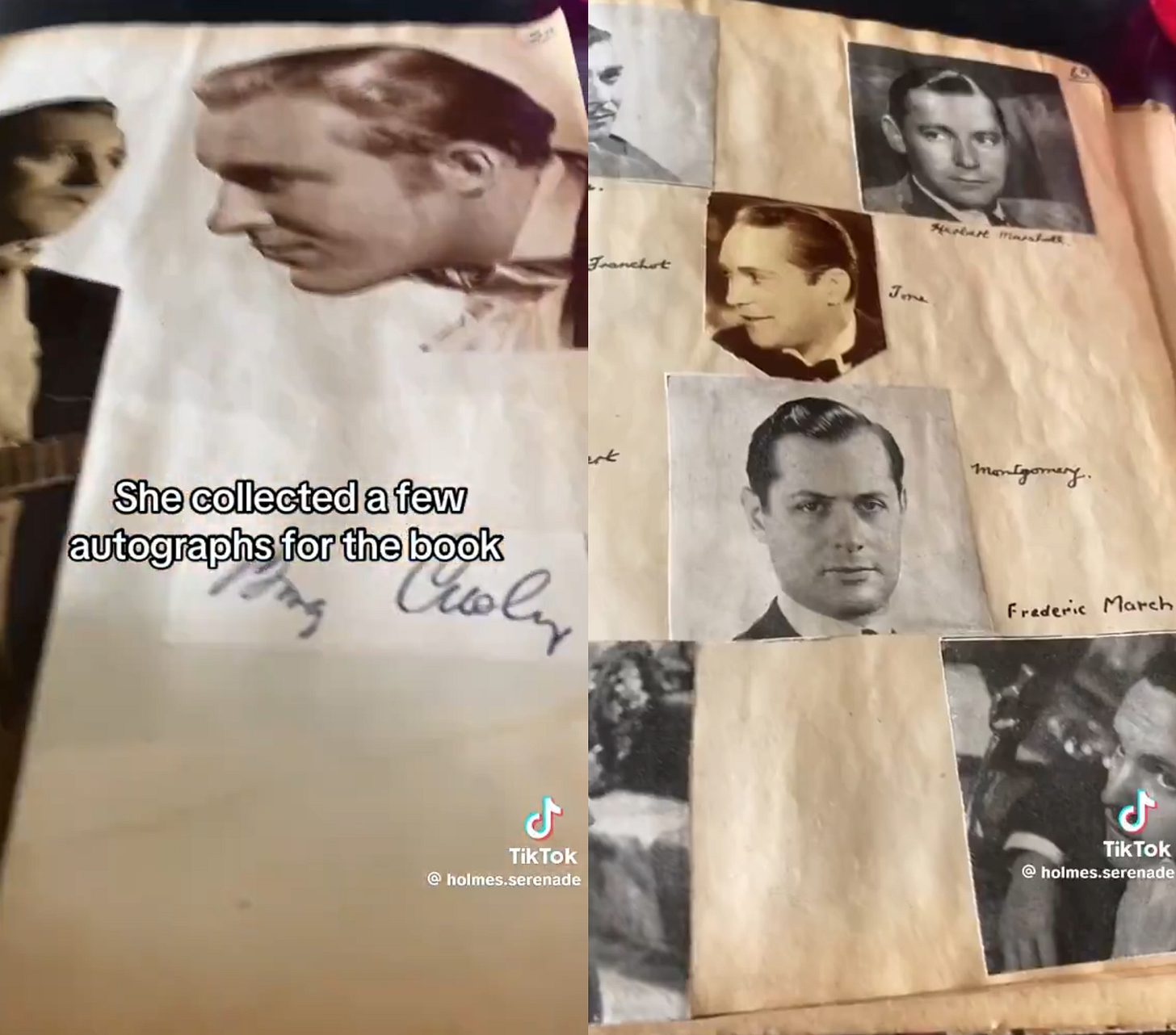

This TikTok (from a now-private account) was reposted on X two days ago by @sexiestbadg1rl with the caption “wow we never really changed.” It depicts a lovingly-crafted Hollywood fangirl scrapbook from the 1930s:

If I had seen this in its original context I would’ve been absolutely overjoyed — I’m an ephemera enthusiast in general, and I especially love vintage fan objects like this one.

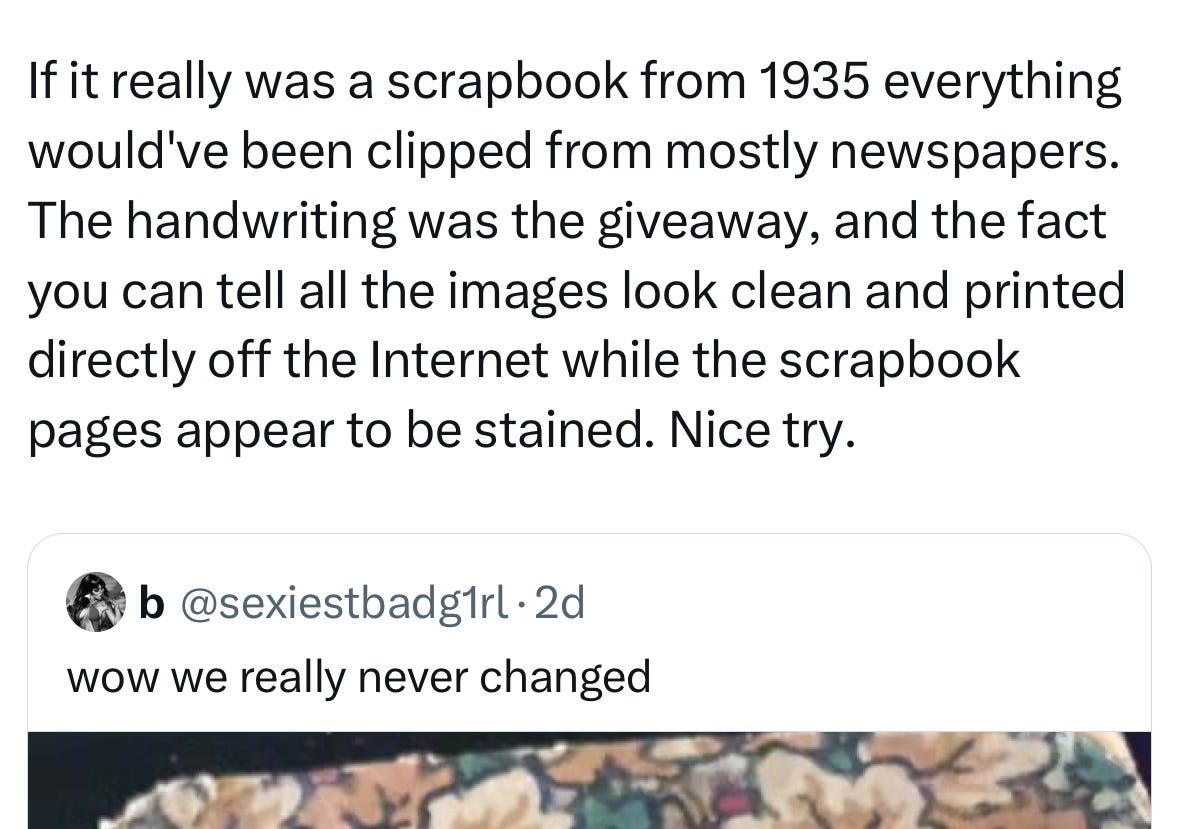

But, having deleted TikTok a few months ago, the way it came across my timeline was through the quote-retweet of @transeurydice:

This interaction currently has 150k likes and 4.1k RTs, an order of magnitude more than the quoted post. A huge number of people seem incredibly eager to agree with the idea that there was NO POSSIBLE WAY this scrapbook could be authentic.

One of the top replies? “Some of those are 1,000% cut out pieces of printer paper u can tell the distinction between them and the real news paper clippings”

Another: “Lol the paper is wrinkled but the images are somehow flawless (they also show no signs of wear they’re printed relatively recently), the ink is DEFINITELY not bearing any signs of being old”

The original post has hundreds of quotes asserting things like: “If this was real, the person would be wearing a mask and gloves because glue back in like the 1930s was basically acidic like everything else”; “If I had to use one video to describe anachronism, it'd be this.”

Singled out for criticism and “proof” that the book is a modern forgery: the handwriting (nobody apparently wrote in printed letters back then), the signatures (the book would be worth thousands if the signatures were actually real), the quality of the photography (“yes ofc because you could print pictures in 1935”) and, again, the paper:

The original QRT followed up their “debunking” mic-drop with a quote from Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto, arguing that believing the scrapbook is real means playing into the “constant posturing of a universal woman myth.” ….? This made me want to tear my hair out, but we’ll get back into that in a second.

First of all, let’s take a brief look at the history of fannish scrapbooking. The practice of keeping a personal commonplace book was popularized by male scholars, notably John Locke, but by the 19th century (I’m vastly simplifying here) had become a distinctly feminized practice, and middle-class women in America and Britain would collect poetry, imagery, and original writings from friends and family in their personal albums. (For a fantastic examination of how the writings of Byron were collected and transformed by his 19th-century female readers and fans, see Corin Throsby’s 2009 book chapter “Byron, commonplacing and early fan culture”.)

By the turn of the 20th century, mass culture was gaining momentum, and fan culture with it. You could amass large collections of celebrity cartes de visite and other ephemera; you could join a fan club for a matinee idol on the London or New York stage; and soon enough you could visit a nickelodeon and pay to see your favorite silent picture over and over.

Early cinema producers and distributors took advantage of the existing enthusiasm for celebrities and performers in order to stoke interest in their products. “Screen-struck girls” even before the Great War were buying cinema magazines like Photoplay and Motion Picture Story en masse, and many proceeded to transform them into artifacts that demonstrated the emotional attachment they had to the stars of the screen. Kathryn H. Fuller’s work on early film-going culture is a great look into this process. “Movie fan culture,” she writes in At The Picture Show (1996), “started with material provided by the film industry and then was re-created as scrapbooks, poems, fan letters to the magazines and the stars, and fan-written film scripts—all created by moviegoers for their own enjoyment.”

And mind you, this was in the 1910s! By the 1930s, film fan scrapbook culture was so ubiquitous that you can go on Ebay right now and buy an authentic vintage Hollywood scrapbook, much like the one in the original video, for less than the price of a nice meal out. In Diana W. Anselmo’s excellent book A Queer Way of Feeling: Girl Fans and Personal Archives of Early Hollywood (2023), she describes how movie studios and magazines incentivized scrapbooking as a way to retain fans’ attention and “counteract the intrinsic ephemerality of filmgoing.”

She also notes the importance of these scrapbooks when it comes to studying the how and the why of early female movie-going practices, and the ways in which participation in commercial mass culture could be turned intimate, personal, and even queered:

[P]aper-based fan repositories bring into sharp relief the transformative labor performed by female audiences across history. In the creative hands of early moviegoing girls, teleological paper scraps and heteronormative narratives reemerge as refractive artifacts, cropped and decontextualized, turned polysemic with lust, willfulness, curiosity, possibility, and self-affirming verve, characteristics Sara Ahmed identifies as symptomatic of queerness’s “stubborn attachment to an unassimilable difference.”

The array of errors made by the X commentators in assessing the authenticity of the scrapbook are distressing enough: nobody seems to have had any experience holding or touching or seeing a letter or album page from that era. Nobody seems to know what a glossy film magazine is, or understand that a careful cut-out from a high-quality film fan magazine from 1935, lightly adhered to a piece of acidic scrapbook paper and then held tightly between the pages since then, rarely exposed to the sun, would look pretty much exactly how the photos in the scrapbook look. The backing paper is probably of lesser quality than the magazine paper, hence the diverging appearances as they aged.

The complete brainrot of believing that photographs owned by an individual can only be produced by printing them from a personal printer, as opposed to being cut from a magazine or printed book, or developed at a photo lab, or reproduced at a copy shop (as Henry Darger did with his collage images around this time), is hard to take seriously, but if a young adult has had no lived experience of any kind of tactile print culture, I guess this is what can happen.

Anyway, 90 years ago was literally not that long ago. It’s not as if it’s a medieval manuscript! It’s not as if Old Hollywood stars all had their portraits taken on tintypes! I have an envelope of family pictures from the 1920s that are as clear and glossy as the day they were developed. It’s a fascinating phenomenon that analog artifacts can come off as fundamentally inauthentic to people who have little experience with them. It may seem counter-intuitive that gelatin silver photography from the 19th and 20th century can be vastly more high-definition than digital photography from the 2000s—but it’s true.

Consulting a well-preserved and extremely authentic fangirl scrapbook from 1913 last year, I was presented with beautiful pages that very much resembled the ones being debated here. It was a privilege to come into contact with the analog enthusiasm of someone I could empathize with so powerfully across the decades. Sheer ignorance of the realities of the life-cycles of paper and ink aside, it’s upsetting to me to see so many young people, women in particular, dismiss the very idea that a girl almost a hundred years ago could be as exuberantly devoted to the film stars of her day as girls are today to contemporary celebrities.

There is such seeming desperation, such active reaching for proof it isn’t real, because if it was, that would mean that they, today, with their home printers and merch and photocards, are… what? Less unique? I’m not really sure. I just know that the dedication to holding one’s era up as exceptional and alive, and the past as backwards, inaccessible, disintegrated into dust, puts one’s ability to properly consider one’s own context in a chokehold.

In fact, the actual Old Hollywood stans out there on X are agreed on the book’s authenticity, mainly because they have the contextual knowledge to understand who Franchot Tone even was, and that of course a girl back then would like him in ways nobody today would. The idea of going to the effort to fake something like this for Franchot Tone fan clout is laughable.

As frustrating as this discussion has been to watch unfold while I stand by, powerless to make people understand the existence of magazines, it has been really eye-opening—and motivating, in terms of understanding the urgency of my own work. Quite the inverse of being squeezed into a “universal woman myth,” as the OP of that first dismissive QRT put it, taking seriously the material culture of ordinary young women throughout history presents a perfect opportunity to attempt to situate our knowledge in the everyday, and indeed practice Donna Haraway’s own concept of “partial perspective” — which, she tells us, can allow us to “[construct] worlds less organized by axes of domination” (Simians, Cyborgs, and Women, 1991).

I’m trying to look on the bright side here… amongst all the thousands of people unable or unwilling to perceive the authentic charm and beauty of the scrapbook, instead dismissing it as a hoax, I hope there are at least a few people who find themselves fascinated by what it says about the congruence between the present and the past, and newly motivated to begin exploring the kaleidoscopic and inspiring world of paper ephemera.

Published lately

It’s been a while since my last newsletter, so here are some clips I’ve put out since then:

A New Documentary Charts the Sinking of Shackleton's ‘Endurance’—and Its Rediscovery a Century Later for Conde Nast Traveller (10/25/24)

‘BBL Drizzy’ Was the Beginning of the Future of AI Music for WIRED (10/28/24)

Do you have a celebrity twin? The surprising science behind doppelgängers for National Geographic (11/22/24)

The Fairy Tale We’ve Been Retelling for 125 Years for The Atlantic (11/23/24)

Fringe with benefits: Why Americans flock to Scotland to discover the next big thing for Sherwood (12/19/24)

thank you (you, personally!) so much for addressing this debacle!! I regularly work with 1920s/30s ephemera and have been quietly despairing at people's sneering disbelief in the scrapbook. (btw the OP posted her etsy receipt in a tiktok verifying its authenticity!!!)

Wow, I would’ve believed those tweets without much critical thought. Thank you for teaching me something today!!